Simplify writing code with deliberate commits

Do you ever find yourself juggling an ever growing list of things to think about when you are working on a feature? Do you find yourself losing track of what needs to be done next to make progress? If you do (and, spoiler, we all do), then this is the talk for you.

One tool that we under use to help us keep focused and keep our work simple is our source control system. In this talk I will outline some habits and practical techniques to apply to your local development workflow with git that can help simplify the development of software in complex, real world environments and make you a better software developer. These include

- Planning your commits

- Making atomic commits

- Writing commit messages that provide context to your decisions

- Ensuring that each of your development branches has a single purpose

- Regularly using

git rebase --interactiveto ensure your development branches tell a clear story about the work that you are doing

A neat side effect of these approaches is that they will give you the added bonus of well documented code that is easier for your colleagues to review and/or make sense of in future

📄 Transcript

This transcript is from a version of the talk I gave at Frontend London in May 2019.

I want to start with a quote, “If you can’t explain it simply you don’t understand it well enough”. This is often attributed to Albert Einstein.

It may not have been said by him but I think he would have meant it. He was talking about physics, if he said it, but I think it applies equally well to our jobs and the code we write. If we can’t explain our code simply then we don’t understand it well enough.

There was a huge change for me in how I developed software when I started using git, over a decade ago.

The flexibility it offered in terms of how you can play with commits, create branches easily, merge commits, split commits up, amend commits, changed the way that I thought about using my version control system.

Before that it was just a place to keep all the old versions of my code, which is great, better than just renaming files in directories which I had been doing beforehand but now it was a tool which helped me understand the work I was doing. I want to share with you some of the practices that helped with that.

It is also problematic because it takes discipline and willpower, which takes up space in our heads, for a few good reasons.

Firstly we are all optimists. Some of you will be shaking your heads and thinking, “I am not an optimist”, but look at the estimates we make for how much time it will take to develop a particular piece of software and I think it is clear that we are all optimists. We are all optimistic about how easy a problem is going to be to solve and I think this is really valuable. If we weren’t optimists we might struggle to come into work in the morning and believe we are going to be able to fix all these problems.

I think we are also optimists about the size of our brains. We are all smart people working on complex problems and we imagine we can hold a lot more complexity in our brains than we really can and we overestimate our ability to handle complexity.

Secondly, we are all impatient. We get excited by finishing the problem, by showing the working software and so we want to get to the end as soon as possible. That comes from a good place but it does mean that we are tempted to make much more complex steps than really make sense and then we get slowed down, get caught in the weeds, and it takes much longer than it would otherwise.

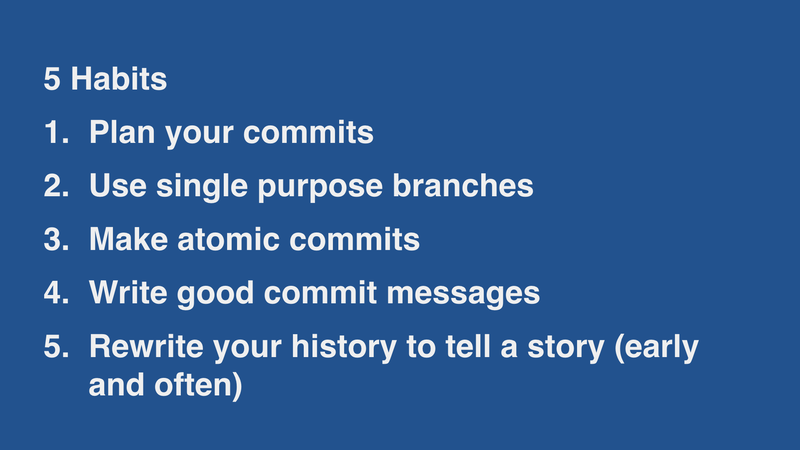

I will take you through 5 habits that I think will really help

- Plan your commits

- Use single purpose branches

- Make atomic commits

- Write good commit messages

- Rewrite your history to tell a story (early and often)

Some of you will be sitting there thinking, “When I start working on a problem I don’t know enough to make a plan”. I would argue that if you don’t know enough to make a plan then maybe you aren’t ready to write production code yet.

There is all sorts of work you can do to make the plan, to understand the problem better. You can read the code to better understand how your current system works. You may even write code, do a ‘spike’, to better understand how you might solve the problem. The focus should be how can I learn enough to make a plan.

Some of you will be thinking, “When I write code I am always discovering new things as I work and my plan changes all the time so why bother making a plan?”. But if you understand the problem well, making a plan is relatively simple.

If you discover new things then having a plan to compare against is really useful. Have I just added one more step that I had forgotten about? Great. Or am I now veering way off course and maybe should be asking the questions, am I still on the right track or do I need to take a bigger step back?

Plan your commits ahead of time and re-plan when you need to.

If the plan is more than 2 or 3 steps long then write it down. Stop yourself needing to keep it in your working memory.

You want to keep focussed on this purpose and this is easier said than done. Quite often you will notice that you have moved away from the work you were originally doing.

Again this can often be for very good reasons. As you open a new file perhaps you notice a typo or some outdated comments which are nothing to do with what you are working on at the moment. As a good developer you want to tidy that up and that’s brilliant but it’s not pertaining to the work you are doing right now.

If you stop and notice this then you can decide what to do.

Maybe you need to fix it now, perhaps this is a bug that needs sorting out. If so, then create a new branch and fix it there and then return to your work. Alternatively just write it down as something you are going to go back to, once you have finished this piece of work then you can go back to fix it up.

Another thing that is really helpful to do is notice if the commit you have made has value independently of the feature or bug you are working on.

A good test of this is to imagine that you come into work tomorrow and the feature you are working on is cancelled would you still want this commit in your code base.

Quite often you will. Perhaps you have been refactoring a bit of the code to make it easier to work on, in which case that commit has value independent of the work you are doing.

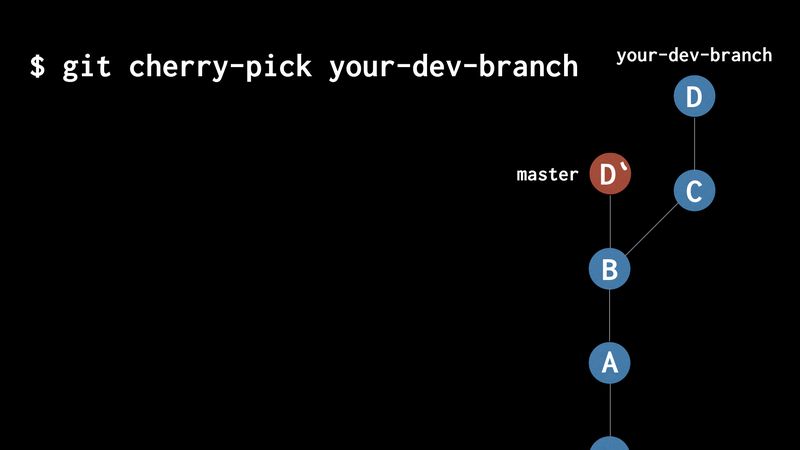

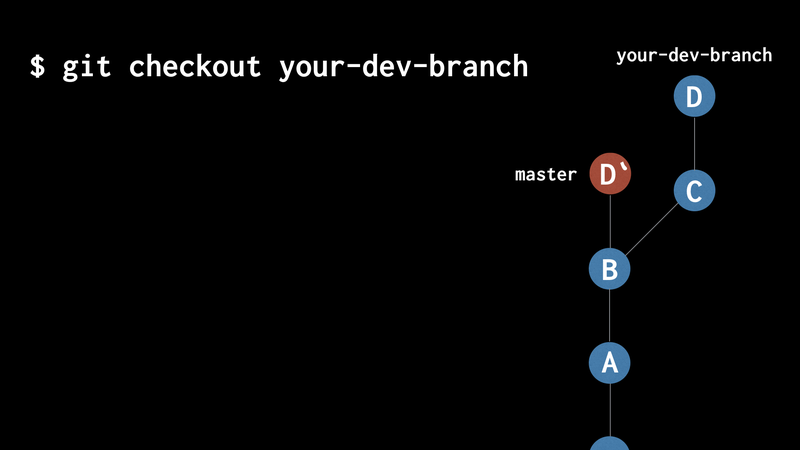

If this is the case then you can ‘cherry-pick’ this commit onto master.

You want to share this code back with your team as soon as possible because it is already making the code base better independently of the work you are doing.

Some of you will be familiar with git cherry-pick but for those of you

who are not I will talk you through an example

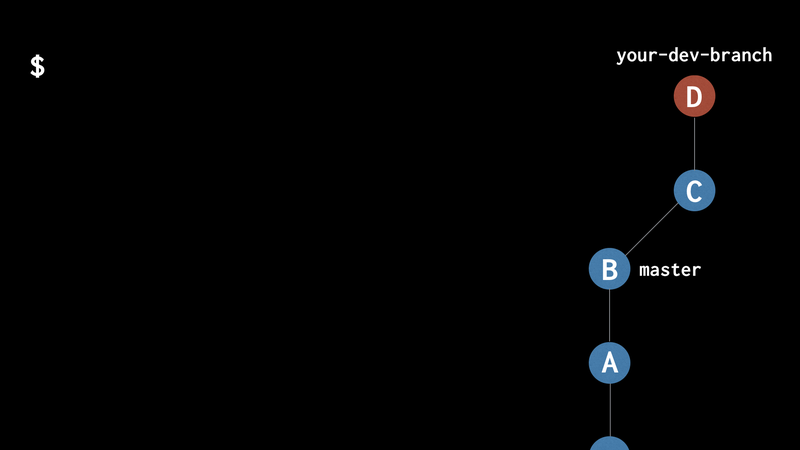

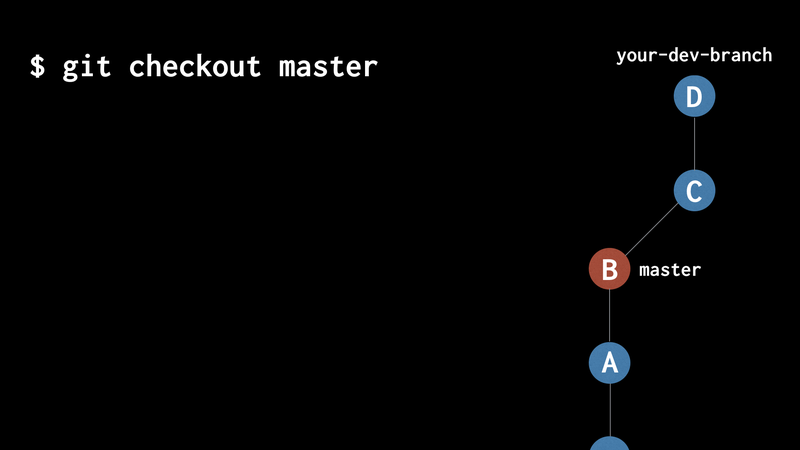

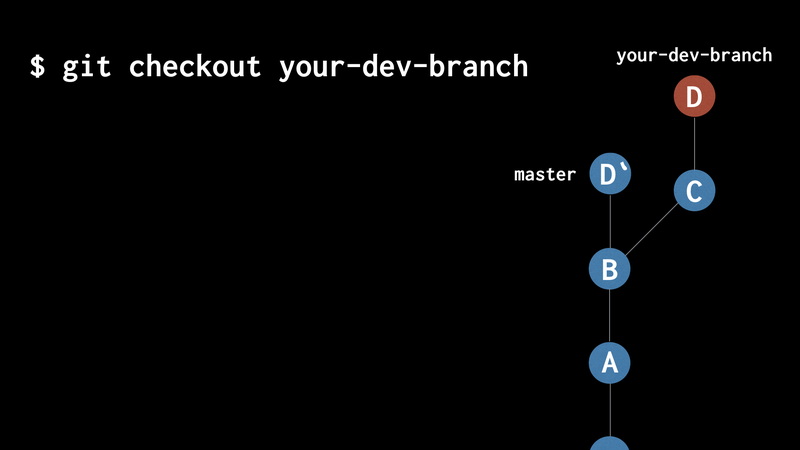

Here’s an imaginary history of a git project.

We have commit A, and then commit B where master is, and then you have

created your own development branch with commits C and D and I have

coloured commit D red to show where HEAD is at the moment. That’s the

branch you are currently on.

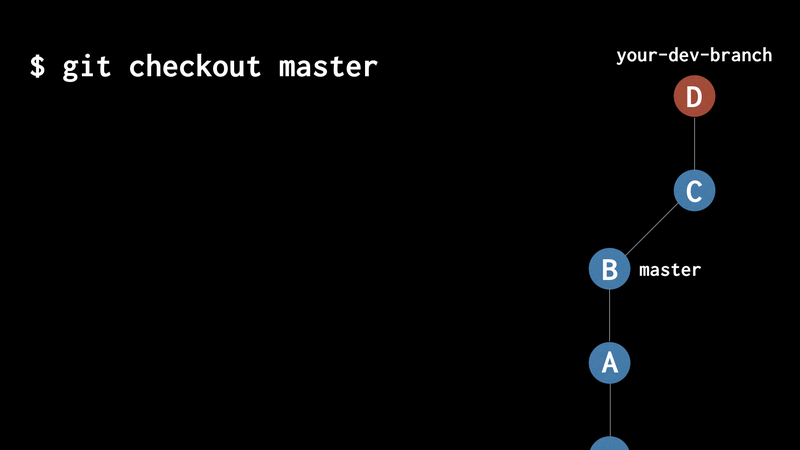

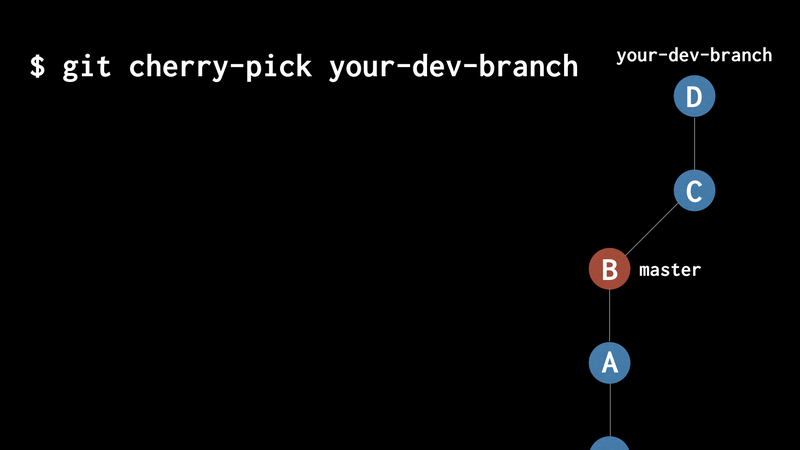

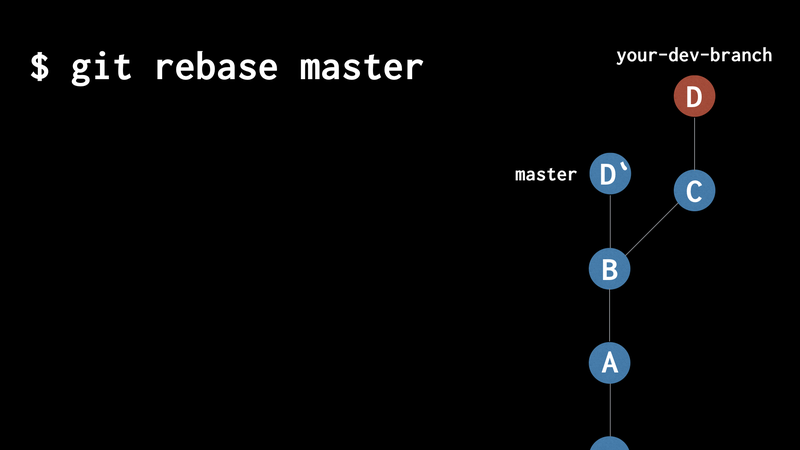

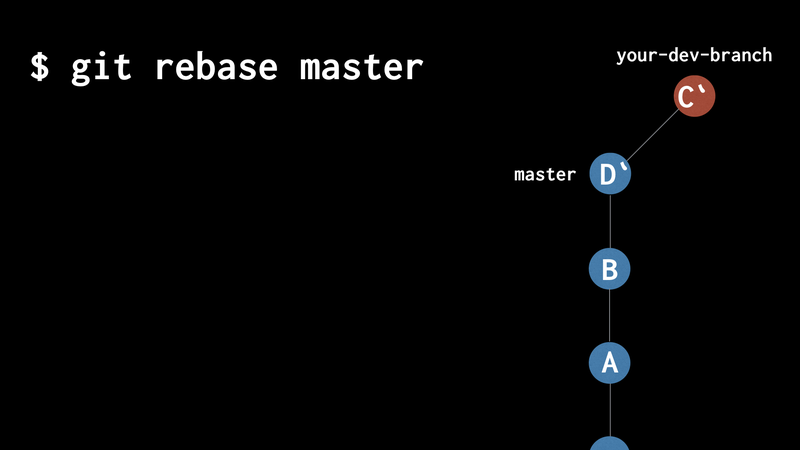

SHA but if the commit you want is at the HEAD of a branch then you can

use the branch name so that’s what I have done here - git cherry-pick your-dev-branch and that will cherry pick D and put it on master.When I talk about this people often ask me, “How big a change should I make?”

In general, in our communities, people make their commits too big, they put too many things in them. If you are in any doubt at all make them smaller.

There’s another reason for making them smaller. It’s quite easy to merge commits back together if you have made lots of little commits but it’s very hard to split commits again. Starting small means you can change your mind later but starting big means you are stuck.

Again you are going to have to start noticing when you start doing something else.

This is really easy to do. You get something working and then, great, you want to get onto the next part of your plan and you don’t commit anything you just start this new piece of work. All of a sudden you’ve got 3, 4, 5, 6 changes all sitting there unstaged in your repository.

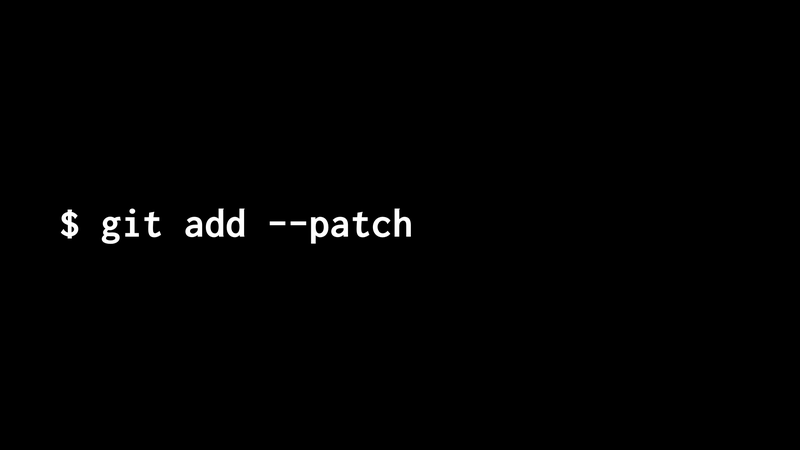

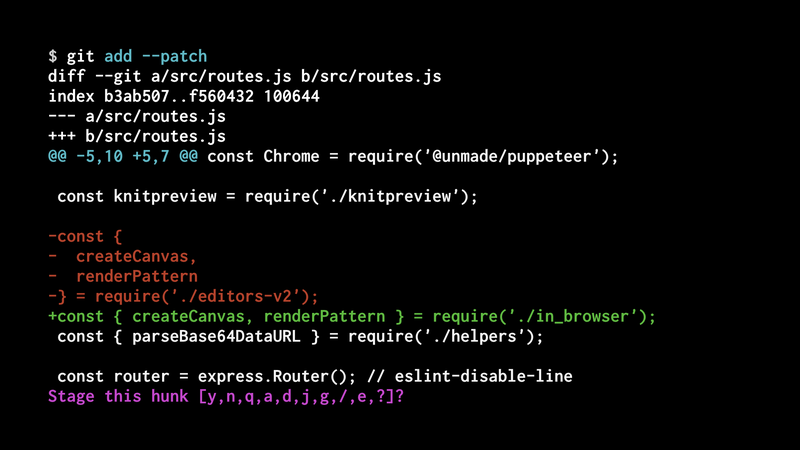

Another useful tool that git offers to help with this is git add --patch.

Normally when you use git add you give it a filename or a directory

and it just adds every change in the file or directory. This makes it

very easy to inadvertently add multiple edit from different sorts of

changes you want to make to your code base.

git add --patch it will walk you through each chunk of

changes you have made in turn and ask you whether you want to stage it

or not. You can say “yes” or “no”. There are other commands to explore

as well, you can split up, or edit etc. but “yes” and “no” will get you

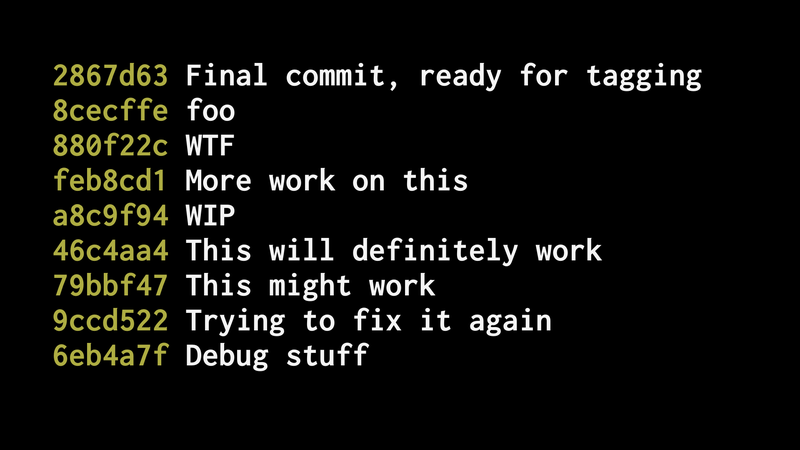

a long way.We all know what bad commit messages look like.

I have written variations of all of these in the past. I didn’t take these from a real project, I used a bad commit message generator available on the internet but you’ve all seen these.

What’s wrong with these messages? They don’t tell you what’s going on. The only way you can tell what’s happened with this history is going into each one and looking at the differences to the code.

We can do better.

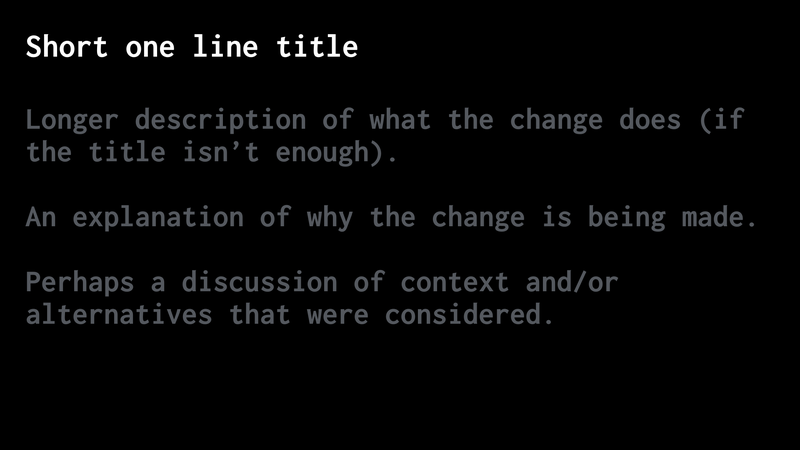

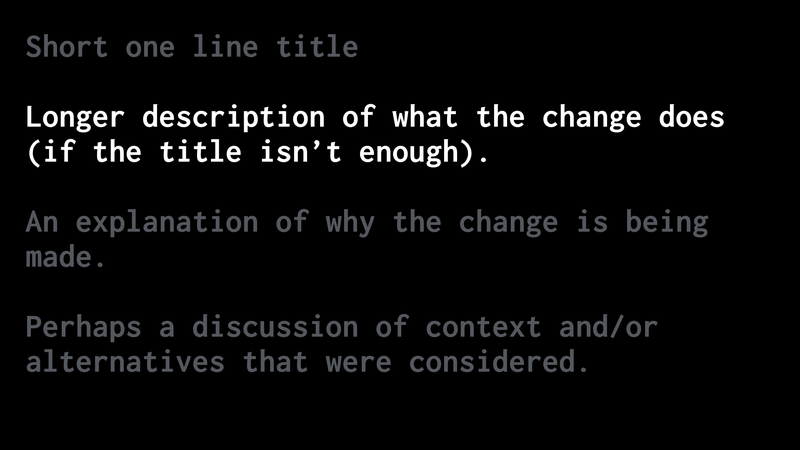

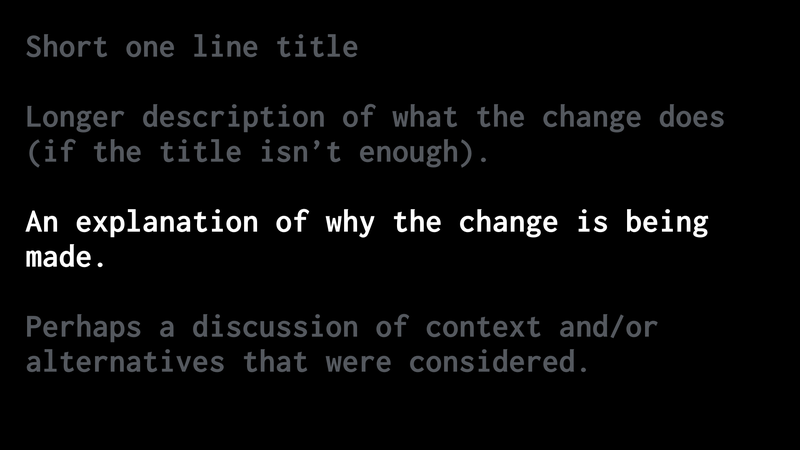

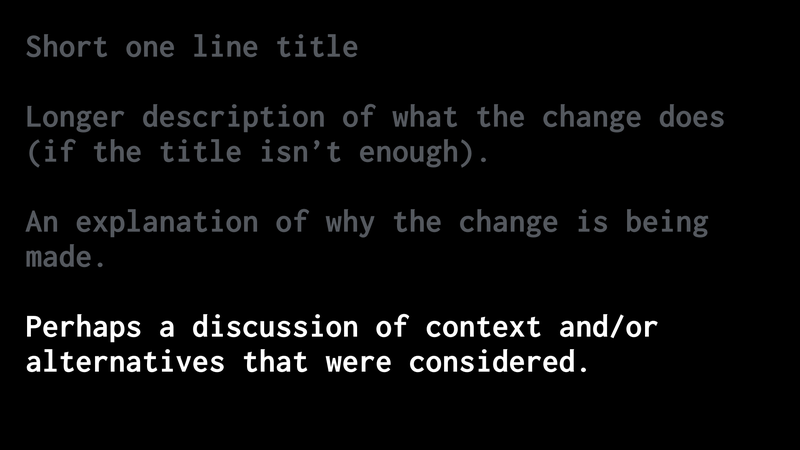

Here’s a template to help you think about this.

Not every bit is required for every commit but it is a useful thing to think through.

Short one line title to show what you have achieved in the commit. This is really important because you will often see lists of commits and so it is this title you will see most of the time.

Another thing that is really useful to add and get out of your head is an explanation of why you made the change.

This information you will forget very quickly. Even the next day when you look back you may have forgotten but if you write it in the commit message then you can always look back at it.

Lastly if it is a more unusual change it can be valuable to provide a discussion of the context or of the alternatives considered.

When you make the commit you will know more about the why and how of all the decisions you made than you ever will ever again and so it’s useful to get this out of your head so you don’t have to remember it.

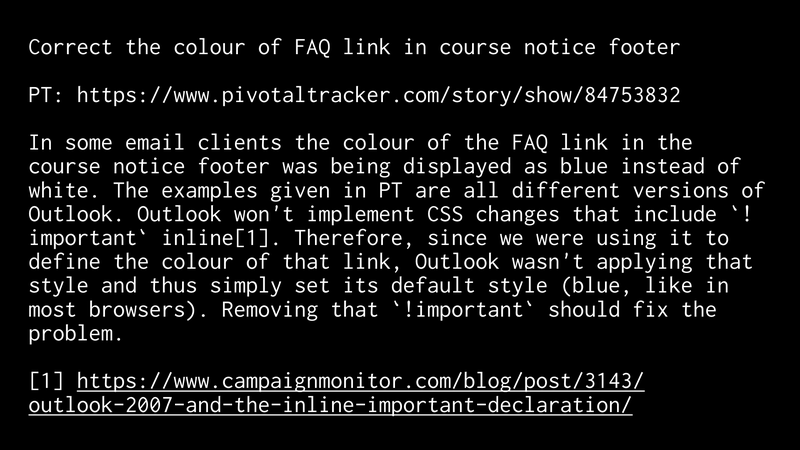

What does this look like in real life?

Here’s an example of a commit message that I didn’t write but I was responsible for the project.

You can see at the top a nice title to explain what has been achieved. Then a link to the project management tool we were using at the time. Then there is a more detailed description of what went on and why we have approached it in the way that we have and a link out to a blog post if you are interested in finding out more.

All of this information no longer needs to be in the head of the engineer who has written it and they can forget about it.

Fifth and final habit. Rewrite your history to tell a simple story and do this early and often.

People who leave this until the end just end up with a mess which is loads of work to rework and is often not worthwhile doing. If you do it early and often it is easy.

git rebase --interactive……which allows you to remove, reorder, edit, merge and split commits.

Effectively it makes your development branch infinitely malleable.

To give you a simple of example of how this works

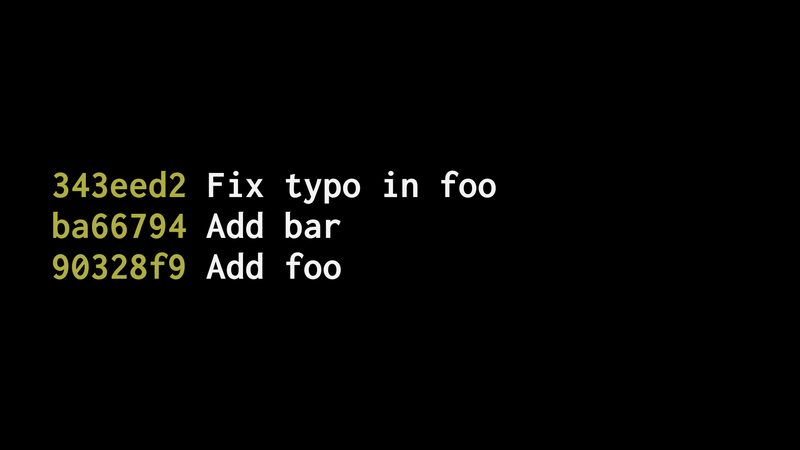

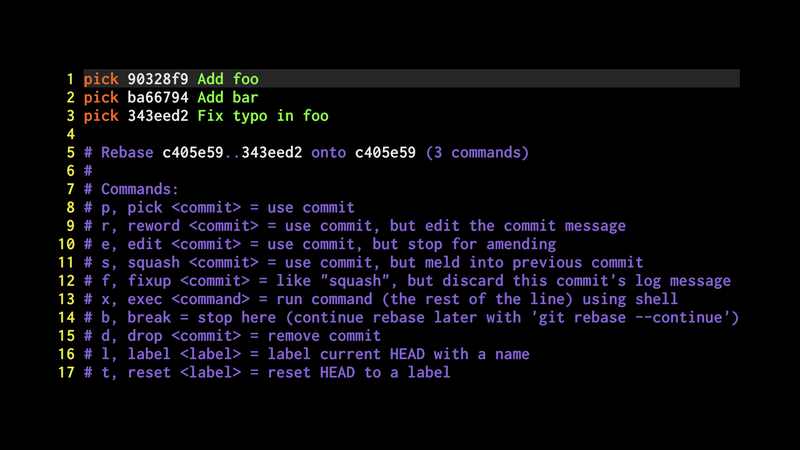

Imagine my plan was to ‘Add foo’ and then ‘Add bar’. But then I notice that I made an error when I first added foo, so I fix it and make one more commit, ‘Fix typo in foo’, giving me this git history.

That last commit is just noise, it’s not really interesting that I made

a mistake first time round, so I can use git rebase --interactive to

tell a simpler story.

git rebase --interactive master, then git will open up that

list of commits in your editor of choice.You can see the three commits I made there ‘Add foo, ‘Add bar’ and ‘Fix typo in foo’.

By default git just picks each commit so if I save this I will just end up with the same list of commits. But you can edit this list. In the comments you can see a good guide to what you can do.

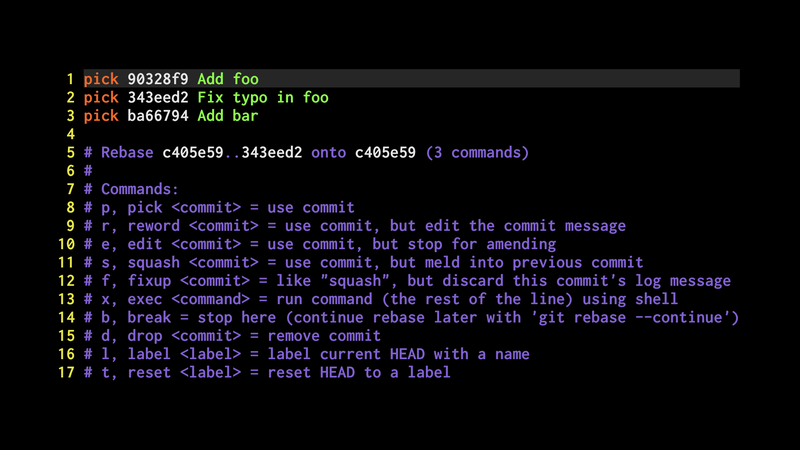

In this example what we will do is…

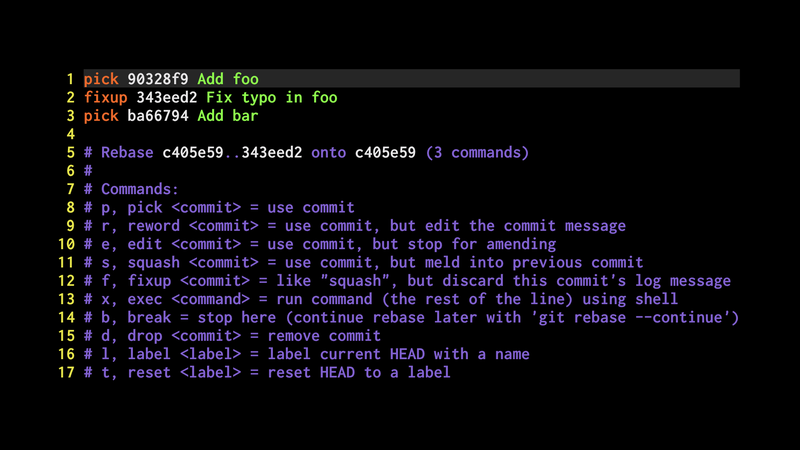

…the second thing I will do is change ‘pick’ to ‘fixup’ for ‘Fix typo in foo’.

‘fixup’ squashes these changes into the previous commit and it throws away the second commit message leaving you with just the previous commit’s message.

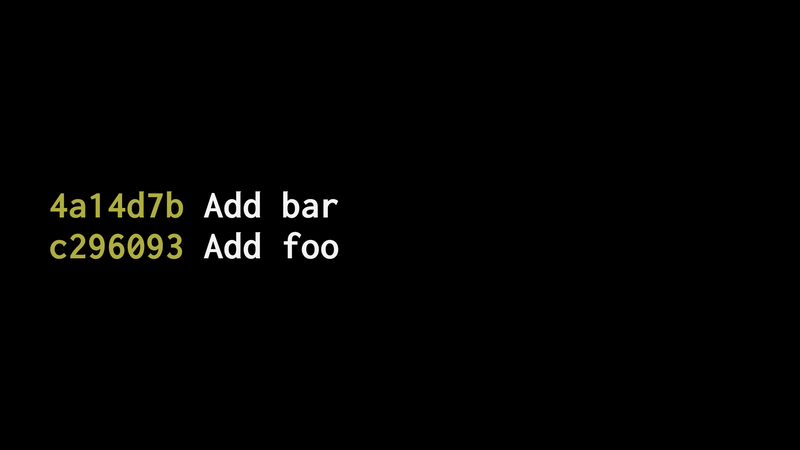

When you save this it will make these changes and leave you with a simpler history, without the noise of the mistakes you made.

This is a simple example but if you have been working on something for a few days there may been quite a lot of that cruft unless you have been cleaning up.

Make your progress clear, so that you can see what you’ve done. That should be a list of nice short commit titles that match with the plan that you’ve got and tell a simple story about what you’ve done.

That will help you understand the work that you have done.

To recap:

- Plan your commits

- Use single purpose branches

- Make atomic commits

- Write good commit messages

- Rewrite your history to tell a story (early and often)

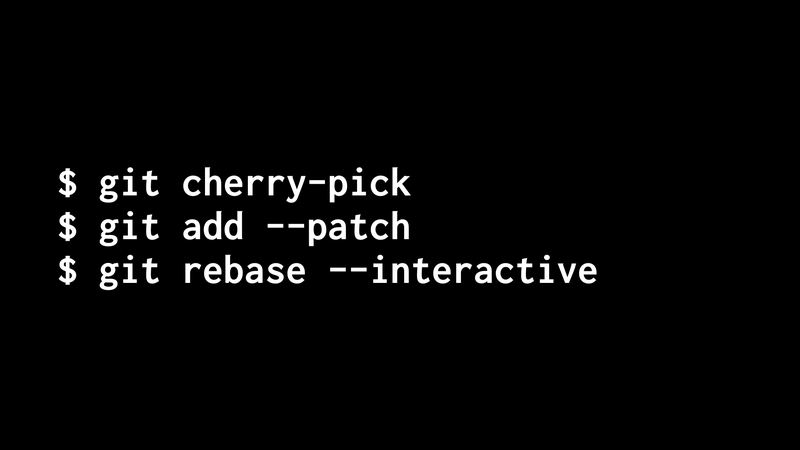

The three git commands I recommended were

git cherry-pickfor pulling a commit from another branch onto the one you are ongit add --patchfor stepping through each change you made and deciding whether to add it to your commitgit rebase --interactiveto rewrite your history to tell a story of what you would have done if you hadn’t made mistakes

Following these 5 habits makes it much easier to work in small steps.

It means you can keep much less in your brain and can focus your brain on solving the problems you face rather than remembering all this cruft.

…it benefits to your team by providing great documentation for all your code.

If you’ve written good commit messages while you have been making

changes then git blame will tell a great story about where a line of

code came from. I have a whole separate talk on this if you are

interested.

But I think the effect on your personal development is more important. Also this means you can benefit from these practices without persuading your team to adopt them too.

📊 Slides

Other versions of this talk

- Jun 2019 - LRUG - Slides

- Mar 2019 - London Python Meetup

Further reading and watching

- Git tips and trick's

Tekin Süleyman's excellent set of articles highlighting practical tips for working more effectively with git

Reactions

Thanks to @joelchippindale for presenting a great five point approach for helping to free up brain space using commits wisely. @python_london

✏️ Edited in Nov 2019 to add the transcript

This is part of a series of talks and articles about the work and practices of my teams and I at Unmade.