This is a short talk about how you can use your source control commit

messages to keep track of the intent of your code changes and make it

easier to keep changing your project in future.

📄 Transcript

I am Joel Chippindale and I have been the CTO at FutureLearn for the

last few years and I am here to talk to you about telling stories

through your commits.

If we have a successful software development project then our key

challenge, as lead developers, is to manage complexity because projects

can get very complex very quickly even within quite small teams.

As lead developers we, and our teams, spend a lot of time thinking about

this. We think about the naming of methods and functions and variables

and…

we think about our code design.

We probably spend a lot of time refactoring code. Taking code that works

and making it simpler to understand.

And probably most of your teams are spending a good proportion of their

time writing automated tests and that allows your teams to have the

confidence to keep changing the software but also helps to document what

the code is supposed to do.

All these tools and techniques help communicate the intent of our

software and if we want to keep changing it we need to understand this

intent.

There is one tool that we under utilise in our communities for

communicating our intent and that is our version control system. All the

examples in this talk use git but the principles apply to whatever

system you are using.

Our commit history has some very special properties which make it

particularly useful for documenting intent.

It is always up to date and this almost certainly not true of most of

the documentation you have, perhaps in a wiki or even in code comments.

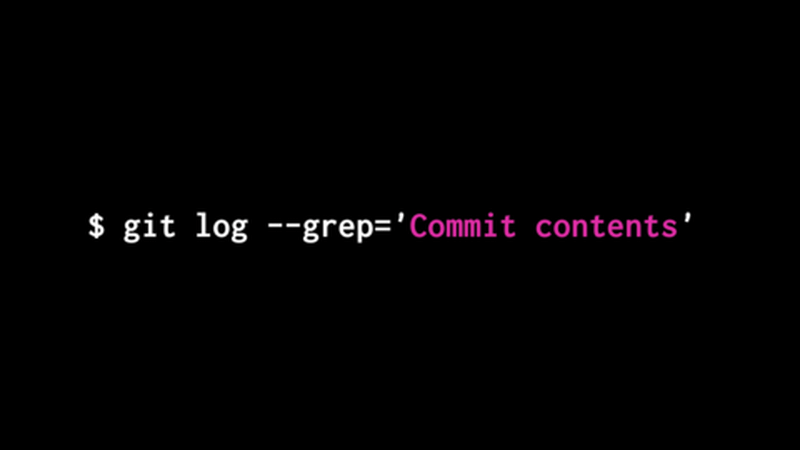

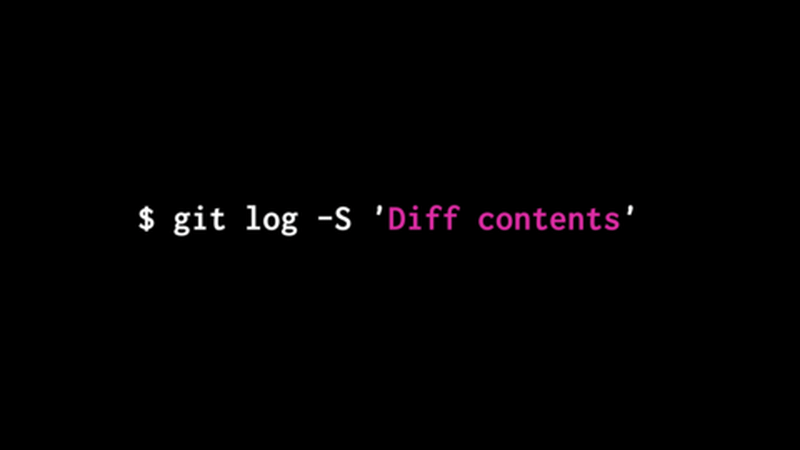

And, this may come as a surprise to some of you, it is searchable. Git

doesn’t make this obvious so here are some commands that you may find

useful.

You can search all the contents of all your commit messages.

You can search all the contents of all the code changes in your commits.

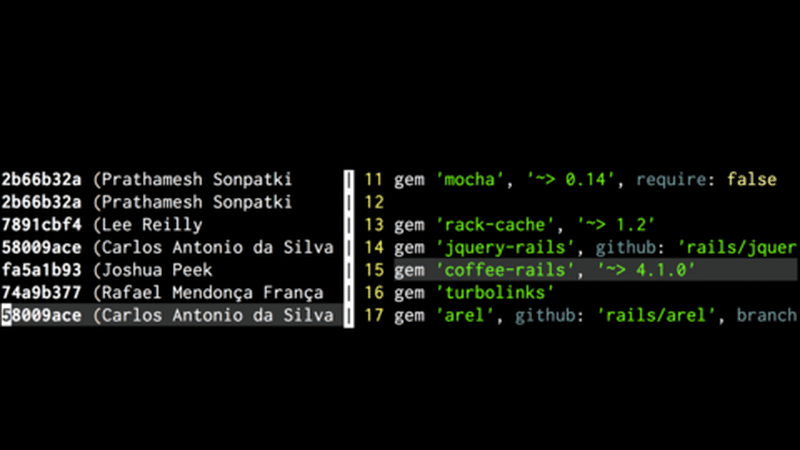

And you can find out where each line of code was last changed…

…giving you output like this.

It is these properties that allow Mislav Marahonić to say that, “Every

line of code is always documented”. If every line of code is documented

how do we make sure that this documentation tells a useful story to us

and our teams about that line of code?

I will share 3 principles with that will help you with this.

Firstly and most importantly make atomic commits. Make your commits

about a single change to your code base.

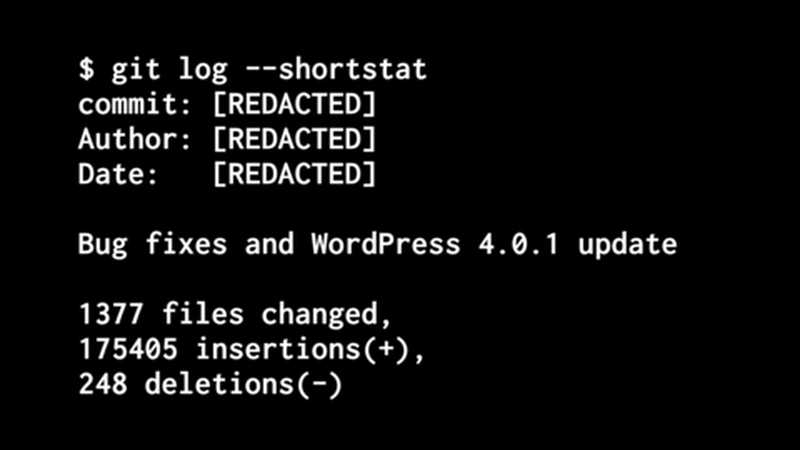

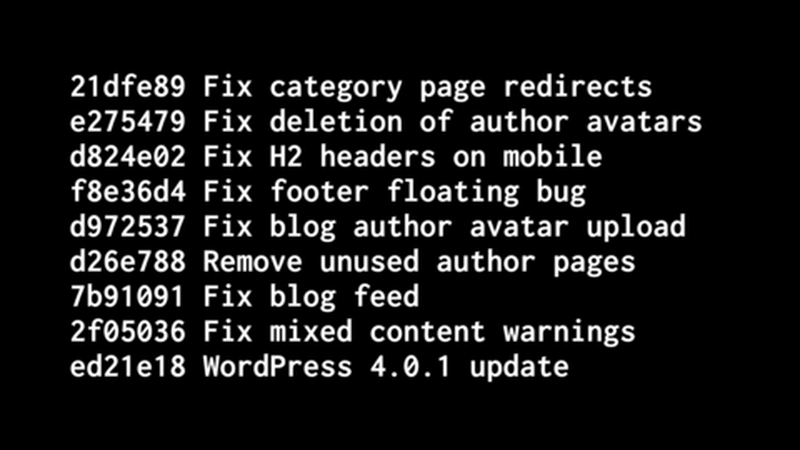

To illustrate why this is important I am going to share a git horror

story with you. This is from a project which I am responsible for. Bug

fixes? Which ones? How many? We have no idea. And a Wordpress update.

Those of you who are laughing are probably doing so because there are

175 thousand lines of code changes in this commit. Reverse engineering

this commit to find out what happened is very hard.

Let us imagine an alternate history where this commit had been split

into atomic commits.

Here we might have a Wordpress update commit containing the vast

majority of those 175k lines of changes and then 8 separate commits each

one about a single bug which is easy to understand.

When I talk about this, I am often asked how big an atomic commit should

be? In our industry we generally make our commits too big so it is worth

thinking about a minimum viable commit. What’s the smallest useful

change that you can make to your codebase?

Another useful rule of thumb is to avoid needing ‘and’ in your commit

messages. If you did ‘A’ and ‘B’ maybe they are two separate changes.

Second principle: write good commit messages.

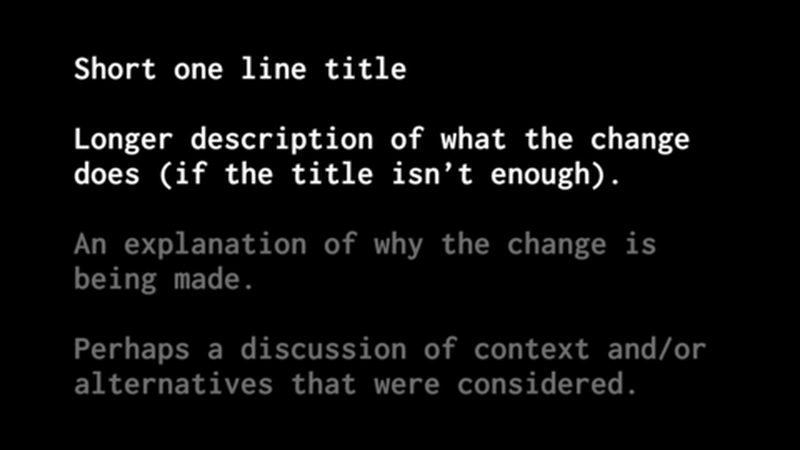

That’s very easy for me to say so I will take you through a template to

give you more of an idea of what I mean.

Short one line title because you view your commits in lists and a longer

description if you need it.

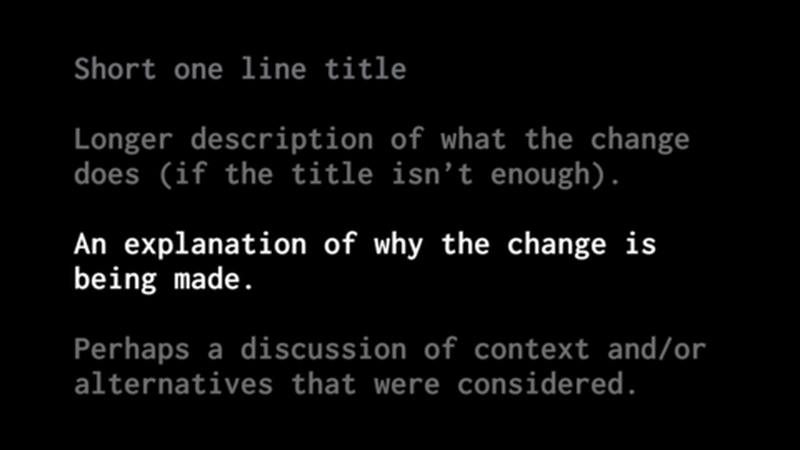

An explanation of why the change is being made. If people want to know

how they can change this in future then they need to know what the

intention of this change was.

Lastly, when you make this commit, you know more about why you are

making this change and how you are fixing or improving this thing than

anyone else ever will and so it can be useful to outline some of the

context and alternative approaches considered.

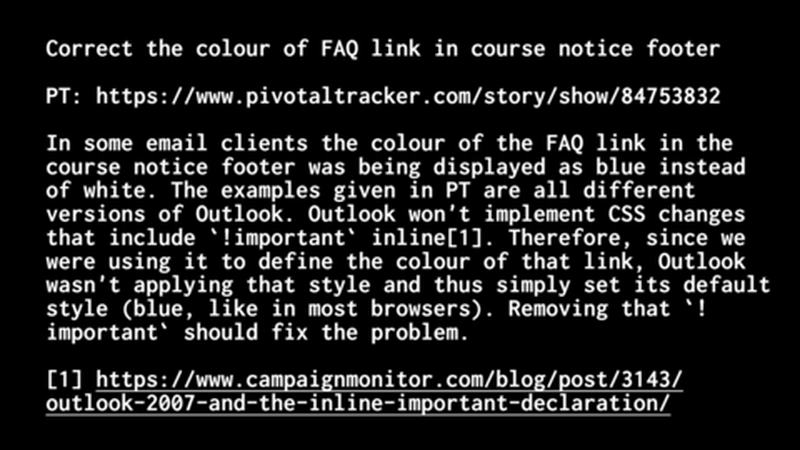

To make this more concrete, here is an example of a commit message from

one of the other projects I am responsible for. You can see the one line

title, you can see a link to our bug tracking system, you can see an

explanation of the quirks of Outlook and why we are making this

particular change and a link to a blog post which explains more about

the problem. This is gold dust for people going back and trying to work

out why the CSS in our project is in the particular state it is in.

Third principle: revise your development history before sharing. We all

know that once commits are on master, or once they are deployed, you

don’t want to change them out from underneath people. But, in your

development branches, it can be much more useful if they tell a story

about what you intended to do instead of a blow by blow account of all

the missteps you took along the way.

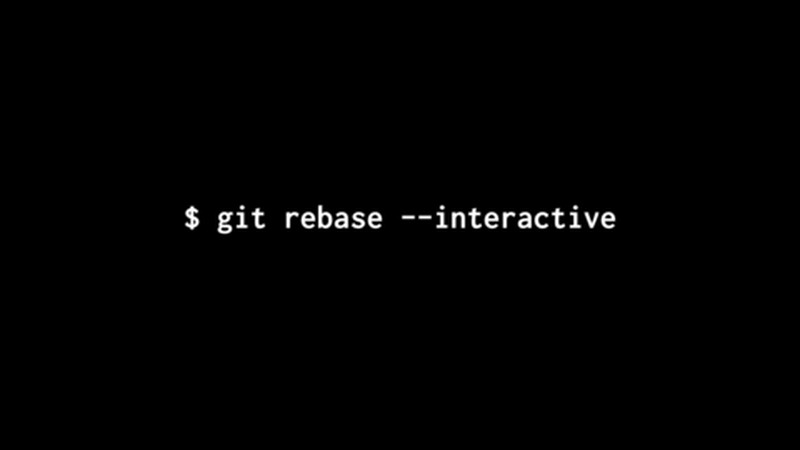

There’s a tool for this, git rebase interactive…

…and this allows you to remove, reorder, edit, merge and split

commits. Essentially with this tool your development branches are

infinitely malleable.

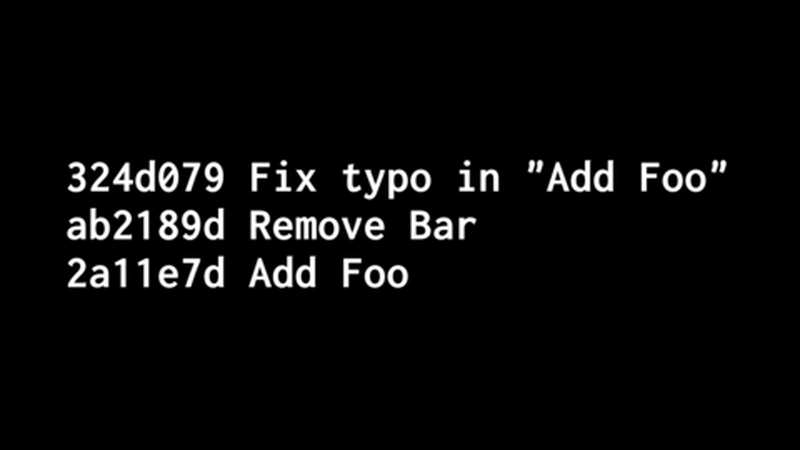

To give you a quick example. Imagine I have added Foo and made a commit,

removed Bar and made a commit and then I have spotted a typo in the

first commit so I make a new commit to fix the typo. That’s just noise

for other people. No one cares about the fact that I didn’t get the

first commit right first time.

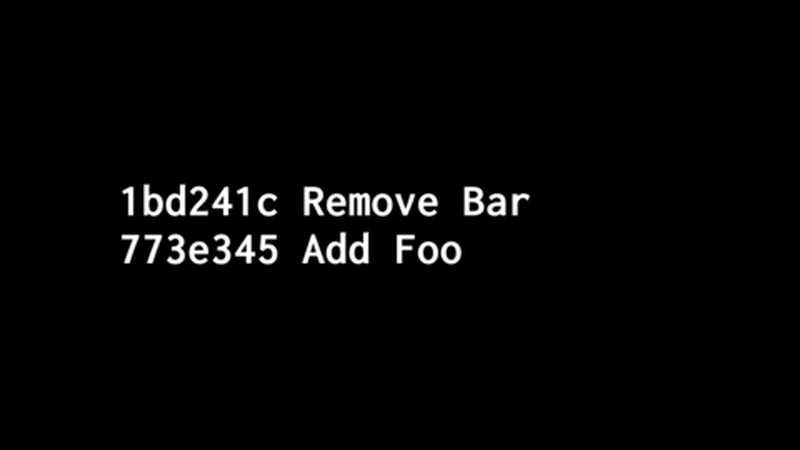

We can use git rebase interactive to merge the first and third commits

and tell a simpler story about what we are trying to do.

So three principles. 1. Make atomic commits. 2. Write good commit

messages and 3. Revise your development history before sharing

This is a quote from someone who joined our team recently which I hope

will help persuade you of the benefits of taking this approach.

Perhaps you are sitting here, as lead developers, thinking this sounds

like a really good idea. How am I going to take this back to my team on

Monday? How am I going to persuade them to adopt these practices that

seem like they have pay off months or even years down the line perhaps

for other developers on the team?

Won’t it take a huge amount of discipline?

I think the key is that all these practices make things simpler for

individual developers in your team right now.

Let’s go back over the principles.

Make atomic commits

This is about making sure that you are making one change at a time to

your code. This makes it simpler to work on.

Write good commit messages

If you can write down what you are trying to do in the particular change

that you are making then you are half way there already and it is a

really valuable discipline for you and your teams to get into.

Revise your history before sharing

If your development branch tells a good story about what you did then it

is easier for you to understand what you did and whether it solves the

problem you had and also it is easier to share with others, perhaps in a

pull request, to get feedback. All these practices making things easier

now for your teams.

👏 Thanks

Thanks to my teams at FutureLearn and Econsultancy for helping develop

and road test these practices on our projects.

📊 Slides

Download the slides

Other versions of this talk

Further reading and watching

Reactions

This may be the best guidance I've seen anywhere on writing a really good commit history. My ideal commit combines code changes, test changes, related documentation updates and some background info in the commit, plus a link to the issue tracker

Simon Willison

Fantastic, succinct source control presentation from @joelchippindale #leaddev

@psyked

It's got to that time where I end up sharing @joelchippindale's excellent Telling stories talk with my co-workers again. Let's just cut to the chase and make this required viewing for everyone intending to write code with other people pls. thx.

Matthew Valentine-House

I really have taken @joelchippindale’s commit message recommendations — www.slideshare.net/joelchippindale/telling-stories... — to heart: github.com/altmetric/embiggen/commit/f7648a9c9c9ea...

Paul Mucur

@joelchippindale since your talk at @lrug I've been learning lots more Git. Proper commits, using rebase -i, squashing and more. Thank you!

@adrjohnston

Absolutely loved this talk. It amazed me how much information he was able to cram in a relatively short talk.

Tim Schraepen

. . . . . . .